Merci beaucoup, Agnès

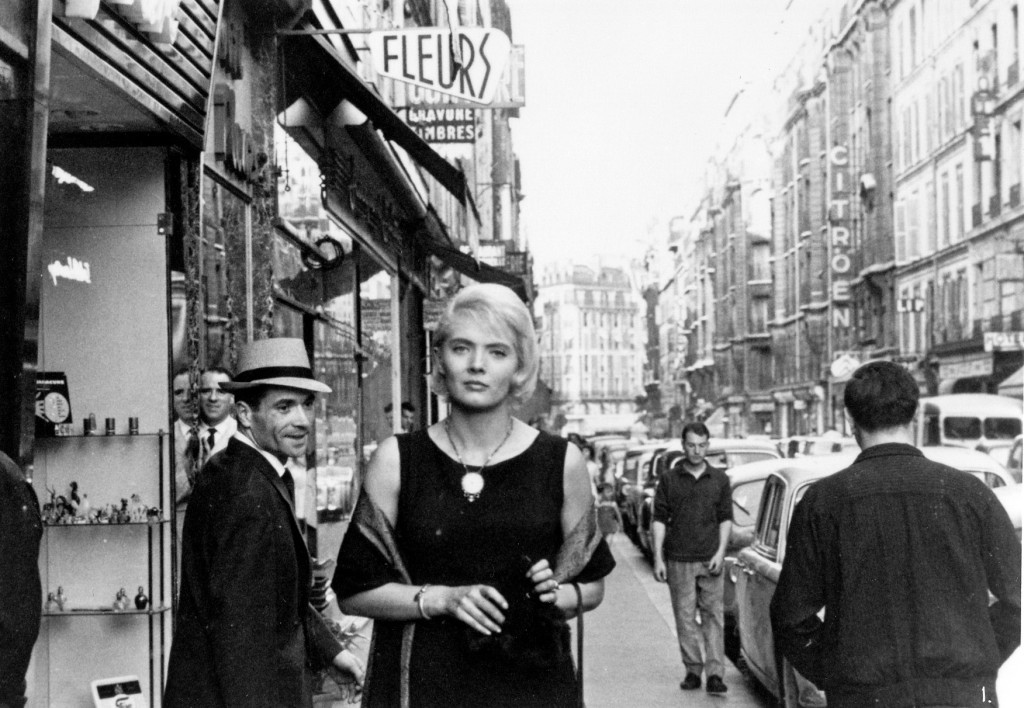

Agnès Varda, who died too soon on Friday at the age of 90, was the tiny, cat-loving, two-tone-bowl-cut-donning matriarch of the French New Wave. She worked as a photographer, artist, and director and is the only woman mentioned in conversation about the New Wave.

When I was seventeen, an account I followed on Instagram posted stills from Le Bonheur a colorful, joyful, and visually refreshing movie directed by Agnès Varda. Both names were unknown to me. With nowhere to rent the film online, I resorted to articles, obsessively scanned through photos, and eventually managed to find a few less than ideal versions of it online. I was stunned by the illusion Agnes created. It looked sweet and tasted bitter. A man with a seemingly perfect family cheats on his wife with a woman that is almost her double. It used sunshine, flowers, and nature as a vessel for infidelity, cruelty, the sourness of a masculine fantasy and its denial of consequence. I had never seen anything like it. Varda herself said it was about taking apart the cliches in a world full of fabricated images of happiness. The worm inside the summer peach.

Later, during my first semester of film school, Varda was the only female director my professor mentioned in a course on the history of French cinema. I finally saw a decent version of Le Bonheur and Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962). At once, her presence was alarmingly inspiring and disappointing. Her work was giant. and the presence of a distinctly female voice made being a filmmaker feel possible. However, the absence of other films made by women was just as large. It was an absence I wanted to fill in the world and in myself, pushing me to seek out more films made by women.

Agnès was concerned with the crowd. The emigrants, the drifters, the passengers, the miners, the factory workers, the artists, the neighbors, and their families. Agnes was concerned with landscapes. The farms, the fields, the streets, the villages, the walls, and the beaches. Everyday things that didn’t feel sublime or complex until you saw her work. They were things that I was always looking at but never really seeing. She was also concerned with herself: her thoughts about life and death and anecdotes about a place she once was long ago. Agnes seamlessly situated herself in the worlds of her work, and her life in her art was only second to the lives of others in her art. Varda saw the importance of the lives that many of us are keen to overlook as well as the importance of paying attention to struggles that are not our own.

Her work looks like a painting, moves like a poem, feels like a lifetime. It has been the most important work I’ve seen in recent years. As a teenager I was completely unsure of my future but absolutely sure I loved movies, even though I only had a basic understanding of them. I didn’t have a favorite director and couldn’t name many that weren’t men. My favorite genre was whatever was playing at the theater that week. I also had a very basic understanding of who I was. Questions about my post-high-school life were met with confusion. I didn’t know where I was going to college or what I was going to study because the dream I had was hard to confront. I wanted to be a filmmaker and I didn’t know how to confess this to anyone, including myself. It felt so unattainable and self-indulgent. How could I think my viewpoints and beliefs mattered or needed to be expressed? What were my beliefs, anyway? Who was I, anyway? Only now can I look back and realize it had to do with the limited exposure I had to movies made by women.

Now, I’m not a teenager anymore. Now I’m a film student trying to find an identity as a filmmaker. I’m still not sure of my future, but now I have Agnès and the other female filmmakers she has led me to. As a woman who is at the very beginning of a life immersed in film, I will spend the rest of mine using her as a mold. As a grand-mère. Agnes will always remind me to pay homage on a large scale, to glean, to see. To make art on my own terms, by my own definitions, and to live life that way too. They are the same, after all. My friend Cristina, a fellow film lover and future filmmaker, said that with every film of Varda’s she watched, she felt herself grow as a woman and as a creator. I feel the same.

Agnès planted us first in 1955, watered us little by little with every successive creation. Now we grow.

In Vagabond (1985), Mona taught me about the complexity of female independence. From 5 to 7, Cléo taught me more than most people will in a lifetime. In Uncle Yanco (1967), Jean Varda taught me that life and death are one in the same. Agnès Varda, and the people in her films, taught me that you and me are one in the same. With her passing I can’t help but imagine the women of the past who weren’t allowed to create due to the limitations of society and accessibility to art and the women like Agnès who did but have been forgotten somewhere, their bodies of work inaccessible. Their bodies nameless and faceless. I imagine the women who are still waiting for us to catch up with their art. She will always remind me to keep chasing it.

Merci beaucoup, Agnès.

Grace Bennett, 20, is a sophomore in college and living in New York City. In 2016, halfway through her first year of business school, she realized she wanted to be a filmmaker. Now she is majoring in Film and Media at FIT with a double minor in English and Art History. She hopes one day to write and direct her own films.